Breast cancer and the environment

Breast cancer's toll

Too many women are diagnosed with breast cancer each year in the United States. A woman born in the U.S. today has a one-in-eight chance of developing invasive breast cancer during her lifetime. It is now the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the country and in the world, surpassing lung cancer. While fewer women are dying from the disease (thanks to advances in early detection and treatment), the number of new cases remains high and continues to rise.

Too many women are diagnosed with breast cancer each year in the United States. A woman born in the U.S. today has a one-in-eight chance of developing invasive breast cancer during her lifetime. It is now the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the country and in the world, surpassing lung cancer. While fewer women are dying from the disease (thanks to advances in early detection and treatment), the number of new cases remains high and continues to rise.

The increase in early-onset breast cancer is especially concerning. Rates are climbing fastest among young women—many of whom are developing the disease just as they are launching their careers and starting families. This trend affects nearly all racial and ethnic groups, with Black women experiencing higher rates than White women. Cases of early onset disease are also rising in Asian American, Indigenous, and Hispanic women.

Adding to the burden is the enormous cost of the disease. According to the National Cancer Institute, breast cancer is the most expensive cancer. Medical costs associated with the disease reached $29.8 billion in 2020. With both the rising cost of new treatments and ever-escalating out-of-pocket expenses, more and more patients are going into debt, reflecting a system of cancer care that is financially unsustainable.

Multiple risk factors

There are many factors that influence a woman’s chances of developing breast cancer. Exposure to radiation, consuming alcohol, postmenopausal weight gain, and not being physically active are well-known risk factors. Women with certain inherited genetic mutations or a strong family history of the disease also have an increased risk.

Another important risk factor is prolonged exposure to estrogen and other hormones that play a role at various stages in a woman’s life. For instance, early menarche (early first period), late menopause, delayed childbearing, or not breastfeeding can increase a woman’s lifelong exposure to estrogen and, as a result, her risk of developing breast cancer.

Rates are climbing fastest among young women—often just as they’re launching their careers and starting families. This trend affects nearly all racial and ethnic groups.

However, these established risk factors do not account for all cases of breast cancer—far from it. Women can eat right, exercise, and make certain reproductive decisions, and still get breast cancer.

It is worth noting that inherited genetic mutations cannot explain the steep rise in early-onset breast cancers because our genes simply don not change that fast. We also see strong geographic differences in incidence rates: Rates are increasing in 21 states, while elsewhere, rates are stable or even declining. If breast cancer were caused mainly by random mutations, we would not expect rates to vary so much by location.

What else might explain the high incidence rates? Mounting evidence—especially for early-onset disease—points to hazardous chemicals in our everyday environment as important and often overlooked contributing factors. These are chemicals we are exposed to through the air we breathe, the food we eat, the water we drink, and the products we use. Many of them have been linked with breast cancer.

The role of environmental chemicals

In the aftermath of World War II, industry began producing large quantities of synthetic chemicals—including pesticides, plastics, solvents, and other substances—with little regard for safety. These chemicals made their way into our everyday products and into our environment. Since then, tens of thousands of chemicals have been produced and sold, the vast majority of which have not been tested for their effects on human health. Even when testing is done by regulatory agencies, current methods do not adequately consider the effects of chemicals on the breast.

In the aftermath of World War II, industry began producing large quantities of synthetic chemicals—including pesticides, plastics, solvents, and other substances—with little regard for safety. These chemicals made their way into our everyday products and into our environment. Since then, tens of thousands of chemicals have been produced and sold, the vast majority of which have not been tested for their effects on human health. Even when testing is done by regulatory agencies, current methods do not adequately consider the effects of chemicals on the breast.

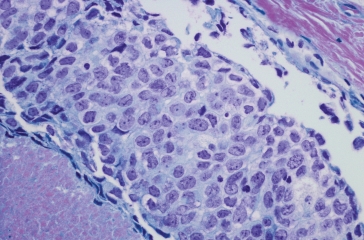

Over the last couple of decades, studies have shown that chemicals can trigger breast cancer in many different ways. They can damage DNA, causing a cancerous tumor to form; they can make breast cells grow uncontrollably; and they can change the way the breast develops, leaving it more vulnerable to carcinogens.

Environmental chemicals can influence the development of breast cancer in many different ways.

Chemicals can:

1. Alter breast development leaving the breast vulnerable to carcinogens

2. Mimic hormones fueling uncontrolled cell growth

3. Damage DNA causing a cancerous tumor to form

Environmental chemicals can influence the development of breast cancer in many different ways.

Chemicals can:

1. Alter breast development leaving the breast vulnerable to carcinogens

2. Mimic hormones fueling uncontrolled cell growth

3. Damage DNA causing a cancerous tumor to form

Environmental chemicals can influence the development of breast cancer in many different ways.

Chemicals can:

1. Alter breast development leaving the breast vulnerable to carcinogens

2. Mimic hormones fueling uncontrolled cell growth

3. Damage DNA causing a cancerous tumor to form

In a study in 2003, we detected dozens of EDCs in air and dust inside the home, demonstrating for the first time that consumer products are a major source of indoor air pollutants.

Scientists are especially interested in a group of chemicals called endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs). These are chemicals that mimic or interfere with the body’s natural system of hormones. Some EDCs cause cells to make more estrogen and progesterone—a known risk factor for breast cancer. EDCs are widespread in personal care products, furniture, food packaging, building materials, and many other everyday items.

In a landmark study published in 2024, researchers at Silent Spring identified 921 chemicals that could promote the development of breast cancer. More than half of them are EDCs and 90 percent are chemicals that people are commonly exposed to in consumer products and the environment. The researchers also found that 414 of the chemicals are used in plastics.

People can be exposed to chemicals in unexpected ways. EDCs can migrate out of items like furniture, build up in indoor air and dust, and enter our bodies. In a study in 2003, Silent Spring scientists detected dozens of EDCs in air and dust inside the home, showing for the first time that everyday consumer products are a major source of indoor air pollution. Silent Spring scientists also made the first measurements of EDCs in drinking water supplies on Cape Cod—highlighting that drinking water is another important route of exposure.

Today, Silent Spring continues to develop innovative screening methods to predict which chemicals may increase breast cancer risk. Our researchers are also studying the human exposome—the full range of environmental exposures over a person’s lifetime—in women firefighters and nurses, uncovering new exposures tied to biological markers associated with early signs of breast cancer.

This work is helping to identify hidden sources of hazardous chemicals in our daily lives and reveal new opportunities to prevent breast cancer and other diseases.

Exposures early in life matter

Studies suggest the origins of breast cancer may occur earlier in life: in the womb, during puberty, and through pregnancy. These critical time periods are commonly referred to as “windows of susceptibility,” developmental stages when an individual may be most vulnerable to chemical exposures.

Studies suggest the origins of breast cancer may occur earlier in life: in the womb, during puberty, and through pregnancy. These critical time periods are commonly referred to as “windows of susceptibility,” developmental stages when an individual may be most vulnerable to chemical exposures.

In a comprehensive review of epidemiology studies, Silent Spring scientists uncovered strong evidence linking early exposures with an increased risk of breast cancer later in life. Early exposures to DDT, dioxins, PFOSA (a type of PFAS), and air pollution, were found to be associated with a two- to five-fold increased risk of breast cancer. Similarly, early exposures in the workplace to high levels of organic solvents and gasoline components was another important risk factor.

One of the clearest examples of the lifelong consequences of early life exposures can be seen in the Child Health and Development Studies (CHDS). In this unique and valuable multigenerational study, researchers collected blood samples from women in the 1950s and ’60s and followed the women and their children to see who developed breast cancer.

The study found that women who were exposed to high levels of DDT before the age of 14, when the pesticide came into widespread use, had a five-fold increased risk of developing breast cancer by age 50. What’s more, when the researchers looked at the daughters, those whose mothers had higher blood levels of DDT during pregnancy had a four-fold increased risk of developing breast cancer later on.

Prevention is possible

Unlike other factors such as genetic susceptibility, environmental chemicals are modifiable risk factors—things we can change. If we can reduce people’s exposures to hazardous chemicals, we can prevent disease.

Unlike other factors such as genetic susceptibility, environmental chemicals are modifiable risk factors—things we can change. If we can reduce people’s exposures to hazardous chemicals, we can prevent disease.

Consider the Women’s Health Initiative study that found postmenopausal women taking combination hormone replacement therapy (HRT) had an increased risk of developing breast cancer, heart disease, stroke, blood clots, and other health issues. Because the risks of taking HRT were found to outweigh the benefits, women stopped taking the drugs starting in 2002. As a result, approximately 12,600 women a year in the United States have been spared a breast cancer diagnosis. Imagine how many more women could be spared a diagnosis if we removed hormone-disrupting chemicals from our environment.

Starting with the publication of the President’s Cancer Panel report on environmental pollutants and cancer in 2010, followed by the Institute of Medicine’s report on breast cancer and the environment, we have begun to see a shift in the way the nation’s physicians and scientists think about how to prevent breast cancer. Many experts are calling for a new emphasis on cancer prevention that is focused on reducing people’s exposures to toxic chemicals.

Through cutting-edge research, we are helping to shape clinical guidelines that integrate environmental risk factors, giving women better tools to reduce their risk of breast cancer.

We cannot wait until a whole community has been exposed to a chemical for decades to see if it causes breast cancer. Instead, we need new strategies now for identifying harmful chemicals and the ways in which people come into contact with them. In other words, when there's strong evidence of harm, we must take steps to protect people’s health.

Silent Spring is leading the way in advancing this approach. Through cutting-edge research, we are helping to shape clinical guidelines that integrate environmental risk factors, giving women better tools to reduce their risk of breast cancer. Our research also supports policies that keep toxic chemicals out of consumer products and guide the development of safer alternatives. By turning science into action, we are working to reduce the burden of breast cancer and create a healthier, more sustainable future for all.