4 government actions that have improved consumer product safety

How science-backed regulations protect people from toxic chemicals in their everyday lives.

How science-backed regulations protect people from toxic chemicals in their everyday lives.

Let’s say you want to avoid exposure to harmful chemicals. You start shopping for a raincoat that doesn’t contain PFAS. But maybe you can’t afford anything you find—and even if you can, you know other companies will keep selling raincoats that contain the chemicals. This means factory workers will continue to be exposed, and PFAS from manufacturing plants will keep leaching into your drinking water.

Buying items made without toxic chemicals can make a difference. When companies see customers choosing non-toxic alternatives, they sometimes decide to change their product formulas.

However, we need strong government regulations as well. “When lawmakers let companies ‘police themselves,’ trusting that they will ‘do the right thing’ on their own, we’ve seen time and time again that corporations prioritize profits over public safety,” writes clean living advocate Lindsay Dahl in her new memoir, Cleaning House: The Fight to Rid Our Homes of Toxic Chemicals. (You can hear Dahl chat with Silent Spring’s Dr. Robin Dodson at our recent Science Café, “The Quest for Safer Products.”)

States often take the lead when it comes to consumer product safety, passing science-based chemical regulations that can eventually result in better national laws. Here are four examples of how science has helped advance state and federal protections for consumers—that is, for all of us.

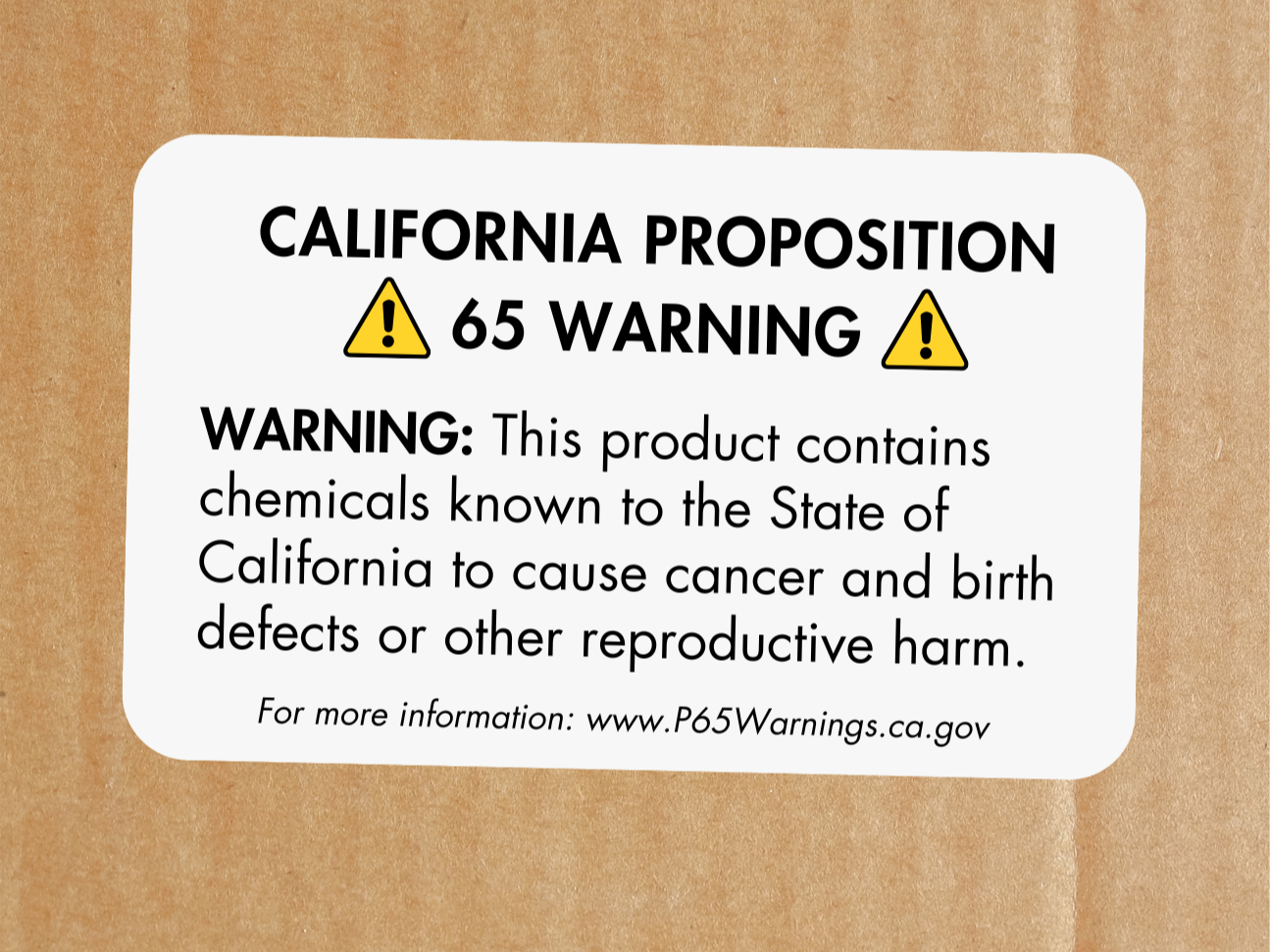

1. Proposition 65

Maybe you’ve seen the ominous labels associated with this 1986 Californian law: This product contains chemicals known to the state of California to cause cancer. You might have wondered, do those warnings actually do anything?

Maybe you’ve seen the ominous labels associated with this 1986 Californian law: This product contains chemicals known to the state of California to cause cancer. You might have wondered, do those warnings actually do anything?

The answer is yes. Proposition 65 requires manufacturers who sell products in California to place a warning on products that contain certain harmful chemicals, and research has shown that the labels work: Companies are reformulating their products to avoid them. “Manufacturers don't want their products described as causing cancer or birth defects,” says Dr. Jennifer Ohayon, an environmental policy expert at Silent Spring and part of a team of researchers who recently evaluated the law.

Many large corporations also don’t want to reformulate their products for different states, so the law has had an impact outside California. Once a chemical is added to the Proposition 65 list, its levels have been found to decline in people’s bodies across the country.

2. The removal of PFAS from food packaging

PFAS are sometimes called “forever chemicals” because they stay in your body and the environment for such a long time. They’re also linked to serious conditions like thyroid disease, immune suppression, decreased fertility, and cancer.

PFAS are sometimes called “forever chemicals” because they stay in your body and the environment for such a long time. They’re also linked to serious conditions like thyroid disease, immune suppression, decreased fertility, and cancer.

One use for PFAS is “grease-proofing.” In a 2017 study, scientists at Silent Spring analyzed 400 food packaging samples from 27 fast food chains, and about half contained PFAS. In a related follow-up, the institute found that people who ate more food at home had significantly lower levels of the chemicals in their bodies.

These and other studies ultimately led a dozen states to ban PFAS in food packaging. Starting around 2016, the FDA also began convincing manufacturers to phase out PFAS for grease-proofing in products that touch food. In 2024, the FDA made an official announcement: Grease-proofing PFAS are no longer being used in food packaging in the United States.

3. The removal of flame retardants from furniture

In the 1970s, concern about fires caused by smoking was growing. To avoid blame, the cigarette industry argued that furniture was too flammable—“which is like saying trees are responsible for forest fires,” Dahl notes in her book—and teamed up with the chemical industry to create flame retardants. The two groups convinced California to pass a law that essentially required furniture to contain the chemicals, which were then added to upholstered items sold across the country.

In the 1970s, concern about fires caused by smoking was growing. To avoid blame, the cigarette industry argued that furniture was too flammable—“which is like saying trees are responsible for forest fires,” Dahl notes in her book—and teamed up with the chemical industry to create flame retardants. The two groups convinced California to pass a law that essentially required furniture to contain the chemicals, which were then added to upholstered items sold across the country.

Flame retardants can cause many health problems, including cancer, decreased fertility, and lower IQ. Two landmark studies by Silent Spring investigating indoor exposures to toxic chemicals in Massachusetts and California found flame retardants in household dust at levels 10 and 200 times those in Europe, respectively. More than 10 years later, another study revealed that flame retardants don’t even improve fire safety.

These findings eventually sparked change at the federal level. As of 2021, manufacturers in California and the rest of the U.S. can meet fire safety standards without having to add flame retardants to furniture. Research by Silent Spring has since shown that swapping out old couches lowers levels of harmful flame retardants in house dust and in people’s bodies.

4. Washington state’s ban on formaldehyde releasers in cosmetics

Seeing the word “formaldehyde” on your shampoo bottle might set off alarm bells. But even if it’s not listed, this well-established carcinogen can still be present. That’s because there’s a whole class of chemicals designed to release it.

Seeing the word “formaldehyde” on your shampoo bottle might set off alarm bells. But even if it’s not listed, this well-established carcinogen can still be present. That’s because there’s a whole class of chemicals designed to release it.

A 2025 Silent Spring study was one of the first to find these formaldehyde-releasing preservatives listed as ingredients in a range of personal care products, including lotions, soaps, hair styling gels, and even eyelash glue. In fact, 53 percent of study participants reported using products with formaldehyde releasers listed on their labels.

These findings have helped inspire a significant first step in regulating the chemicals. Last year, Washington became the first U.S. state to ban 25 formaldehyde-releasing preservatives in cosmetics. The new law lends support to regulations in other states and the Safer Beauty Bill Package, a collection of federal bills yet to be passed that would prohibit the use of formaldehyde releasers and other harmful chemicals in beauty products.

Dr. Robin Dodson, the study’s lead author, says formaldehyde releasers are a great example of why regulation is important. Chemicals that emit formaldehyde are famously numerous and difficult to identify. “Even chemists can have trouble recognizing them on labels,” she says. “We all need strong consumer protections if we want to avoid exposure.”